-

Stimulus-Response Compatibility effects can sometimes reverse

-

It is strongly recommended to read the lesson about stimulus-response compatibility first.

Introduction

Spatial compatibility is an important concept in research regarding attention, perception, and action planning. Typically, people respond faster when a stimulus and response are compatible with one another, for example when they are both on the same side of the body.

Sometimes, the spatial compatibility effect is "reversed". In that situation, people respond more quickly in the stimulus incompatible situation than in the stimulus compatible situation. There are only a few demonstrations of this. For example, one can argue that the Inhibition Of Return (IOR) effect is an example of reversed stimulus-response compatibility (see the lesson about IOR). The example this lesson is about is the ABBA effect, first described by Stoet & Hommel in 1999 (see reading material at the bottom of this lesson).

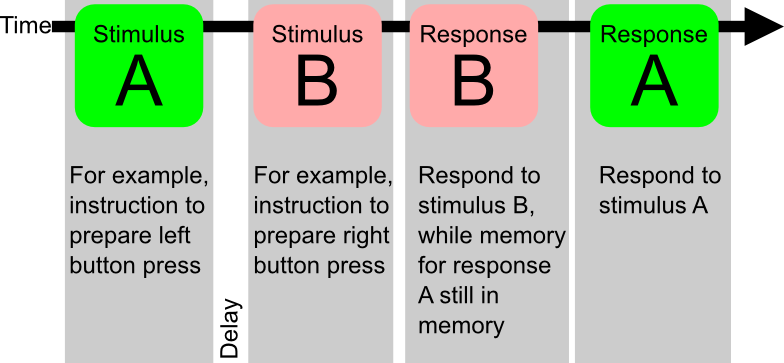

In short, in the ABBA paradigm, you carry out two different responses to two different stimuli. The first stimulus (called Stimulus A) is viewed, a response is planned but withheld until the end of the trial. Then a second stimulus (called Stimulus B) is shown and you must respond immediately (Response B). Then, you must finish the trial with the final response A, which should (hopefully) still linger in short term memory. A whole trial takes around 6 seconds (which will be repeated many times in one experimental session). Below is a schematic picture of a trial in the ABBA paradigm.

Now you understand why it is called ABBA. It is about the sequence of stimuli and responses. You see stimulus B and respond to stimulus B when you are keeping a prepare response in memory. The memory of the prepared response A interferes with the stimulus B - response B task.

The theory behind it is called "code occupation theory". The idea is that if people have used "event" codes to encode response A, these codes are less available for subsequent and different cognitive processes. If the planned response A and the to-be-carried-out response B are on the same side, some of the event codes are already bound in plan A, so to speak. This makes that people are slower to respond with the left finger if a left finger response (or even left foot) response is already been planned and the event code "left" is already bound to a different action plan.

Do it yourself

In this demonstration, you will use four keys of your keyboard, the A and S on the left side, and the K and L on the right side. You plan a response (one or two key presses with the button S or K), and then later you need to respond directly with a A or L key. Detailed instructions are presented in the demo. Note that there are 10 training trials and 100 main trials. The trials run somewhat slowly, because there is a delay of a few seconds between stimulus A and B (during which you just need to wait). At the end, you will see your own response-incompatibility effect.

| In the beginning, this is not an easy task, because the time to respond is fairly short. That said, if you try a couple of times, you will get it. |